The weight of the world

I must start my post with a few disclaimers.

I am not a chiropractor and I have very little to say about the development of a healthy immune system from exposure to pathogens.

I am not (any longer) an urgent care physician working in a suburban practice with a rock star haircut and toned biceps.

I am not a discredited PhD researcher with a bone to pick about chronic fatigue syndrome.

Clearly I am not qualified to share remarks about COVID19 in a meaningful and engaging way.

But I have a few experiences that shape my thinking and I want to be candid about that.

I am a medical doctor, originally from the US, now living and working in a lower-middle income nation for the past 6 1/2 years. Our facility serves a population of about 500,000 people and provides outpatient, inpatient, maternity, surgical, emergency and preventive health services to them.

As part of my work I have focused on public health - including antenatal / maternity care, immunizations, and family planning programs as well as Tuberculosis and HIV clinics. I currently supervise the care of over 1,000 people living with HIV in addition to roughly 300-400 new cases of active Tuberculosis each year.

In my first year in this country I helped our community navigate a measles outbreak (we see it now and again). I saw several babies and children afflicted - some died. The experience made me want to pursue additional training in Public Health and I am completing my thesis this year.

While studying for my Master's in Public Health I have completed courses with really exciting titles such as: Introduction to Epidemiology, Statistics for Public Health, Understanding Health Systems, Advanced Statistical Methods in Epidemiology, Globalization and Health and a real gem called The Epidemiology and Control of Infectious Disease in Developing Countries (or TEACOIDIDC for short.)

So when our first case of Polio emerged some years later I felt I had a little more handle on the kinds of things we needed to put in place to stem the outbreak and felt I was able to partner with our local health authorities to do this.

Fast forward another couple years and there is a new threat: COVID19 - a disease that results from infection with a novel Coronavirus, somewhat comparable to SARS and MERS from years past.

Like a good number of people, I was carried away to devastating levels of worry by the accounts coming out in the early days of the outbreak in places like Italy. Not enough ventilators, patients in hallways, health workers becoming sick (and dying) and some serious unknowns: how exactly is it transmitted, are there any treatments, how long will it take to find a vaccine, why is it so difficult to get testing supplies, etc.

Then a case was confirmed in our country.

I was asked to join our local government's COVID response committee as the public health physician - advising on steps to take to contain and then mitigate the disease in our area through working with various sectors and leaders.

We implemented triage and screening protocols, established an isolation unit, talked about social distancing and did our best to protect the health workers in our area with the very limited supply of PPE that we had through more efficient processes and prioritizing the gear into high-risk activities and departments.

Then the second case was confirmed. Shortly followed by several others, including one within the national government's own COVID response team.

With the country's COVID response team grounded, we had to conduct our own improvised training for health workers on surveillance, infection prevention & control and clinical management. We pressed on, determined to make ourselves as ready as possible.

Patients came to the hospital with all kinds of respiratory complaints. I put on my N95, my glasses, my surgical cap, my scrubs and I washed my hands until my skin cracked. (I still do, Mom - don't worry).

But they also came for everything else. Children with severe diarrhea and malnutrition barely clinging to life. Victims of domestic and tribal violence needing complex orthopedic repairs. Women struggling to give birth requiring operative deliveries. HIV victims wasting away. Tuberculosis cases now presenting in a way frightfully similar to the "new sick". Cancers.

Apparently nobody told these diseases, or those suffering with them, that there was a "lockdown" thanks to COVID - so they just kept marching their path of devastation through this community. And the health system that was already barely able to meet the needs of some of them felt that much more pinched and stretched.

As I now reflect on the nearly 2 months since the first case was announced in our country, I am asking some difficult questions.

A prominent political figure in the US, when talking about how to safely reopen a certain state's economy, said, "A human life is priceless. Period."

Pants on fire.

As Coronavirus makes its way into Africa, many OECD countries are restarting their economies by creating a "new normal" dripping with hand sanitizer and covered in personal protective equipment while waiting to snatch up the first billion or so vials of the upcoming COVID vaccine. It is easier to put a medical face mask on someone entering a reopened casino in my home state than it is to put one on a health worker in my current one.

"Differential valuation of human life runs throughout this commentary and throughout much of the policy designed to address epidemic disease" -Paul Farmer. Is the value of casino-goers in the wealthy world higher than that of health workers in the majority?

But some of that is changing. Solidarity is being shown through the movement of equipment and expertise into places that are just starting to see the virus emerge in their populations. The availability of PPE will be a logistical challenge but continued efforts can minimize the shortfalls. Countries with a proven track record of providing foreign aid and assistance are reaching out and that will be sorely needed for years to come.

But how are these more vulnerable communities and health systems most effectively helped?

To answer this question, we need to understand the impressive differences between places that have already seen explosive outbreaks of COVID19 and those that are just getting started.

While a politician might be obligated to declare a human life "priceless", realistic public health workers in settings with lower resources recognize that this is a fallacy. While New York City hasn't *really* had to ration care for decades, most places in the majority world are already doing it every day. This reality is the "cruel calculus of extreme poverty", as Dr. Hans Rosling said.

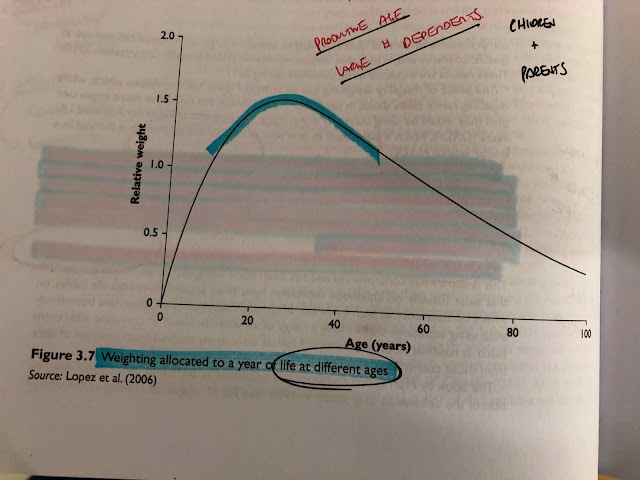

When assessing what health interventions make the most sense, some kind of value or "price" must be used. In my training, this was referred to as "weighting." If someone falls ill and becomes disabled or dies, they have effectively lost either years of life or productive years of life. When you are trying to make every penny count you try to estimate what the "weight" of that person's year of life is compared to another person's. One of the simplest ways to do this is by age.

The relative weight of a year of life is actually highest for those aged about 20-45. These individuals often have a large number of dependents - usually children and, where social security systems are weak, elderly parents. Why does this matter? Because health interventions that target this demographic (for example, women of child-bearing age) tend to have positive effects that go well beyond simply preserving the life of the individual. They sustain the fabric of society. This "cruel calculus" guides decision-makers who have to choose what health interventions to focus on.

This is why family planning and maternal health are such important services to strengthen and invest in - especially in societies with health systems of extremely limited capacities. In the 108 days since COVID19 was declared a public health emergency of international concern, about 85,000 women died due to complications of childbirth.

In a lot of outbreaks, like Polio or Measles, children are more adversely affected than adults. This is true of other diseases like simple diarrhea or pneumonia as well. (This has not necessarily been the case with COVID19.) Children are not productive members of society. Economically - why so much emphasis on child health? Those individuals aged between 20 and 45 will often bankrupt themselves and risk their other dependents' lives while they seek care for an ailing child. If you can keep their children healthy they can focus on keeping their community going. But really, you don't need to argue for the fact that children should not be dying if it can be prevented. In the 108 days since COVID19 was declared a public health emergency of international concern, about 1.5 million children less than 5 years of age died around the world.

In the majority world, there is a contagious disease that has infected and killed millions. For victims in these environments, the conditions that lead to them contracting HIV are the same conditions that lead them to die from it earlier than they would in a high-income country. Many of them acquire HIV in their 20's and, without access to reliable testing and anti-retroviral treatments, go on to die before they reach their 40's. In the 108 days since COVID19 was declared a public health emergency of international concern, about 225,000 people have died of HIV around the world.

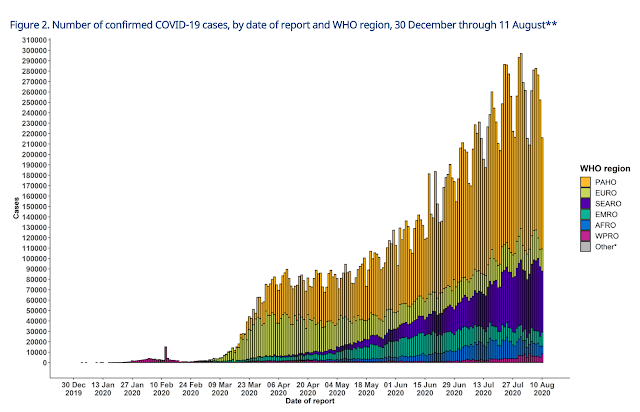

The case numbers for COVID are sobering. Millions of cases and hundreds of thousands of (confirmed) deaths. Where do they fall in this "cruel calculus?"

I use the ICU admission rate by age because in our setting, this will more closely approximate the case fatality rate. There are no ICUs and those who require more than just supplemental oxygen are unlikely to survive a severe COVID infection.

Those aged 20-45 are admitted to the ICU between 2-4.2% of the time. The rate increases impressively as age increases. Obviously there are other factors like co-morbidities and things - and young people can certainly become critically ill and die from COVID - but the majority of severe cases occur in the elderly.

Am I trying to say that their lives are not valuable? Absolutely not.

If you want to approach a potential COVID outbreak from a realistic, population-based public health standpoint you need to understand the disease you are facing, its mode of transmission and who is most susceptible.

A respiratory pathogen that spreads by droplets will be wildly more contagious than, say, HIV - a virus carried in the blood. The extreme measures used to interrupt transmission like "social distancing" and "lockdown" strategies employed by wealthier nations may be impractical and actually harmful in settings where people cannot eat if they do not work and go to their markets.

Similarly, attempting to isolate, test, treat and repeat may be so exhaustive on a health system's resources that it is left bankrupt and fragmented - unable to provide any other essential services. Currently there is speculation in some countries about whether COVID19 has already "come through" and there may be ways to assess this with various testing strategies. But diagnostics represent a massive challenge logistically unless de-centralized tests can be made available in great supply. Further, the stigma associated with a diagnosis of COVID19 may create more harm to the individual and their community than the condition itself. Replicating the testing strategies of high-income nations is a non-starter in settings of already-limited disease surveillance.

|

| My country has conducted about 2,000 tests TOTAL in the two months since the index case |

Isolating, testing and treating (Remdesivir? Oxygen?) can eliminate a disease in theory, but in practice the elimination of COVID19 from countries with weak health systems is most likely impossible without vaccination so for at least a year or two, it may just become yet another endemic tropical fever that can kill them.

So is there a bright side?

Yes.

The age demographics of many countries currently anticipating an expanding number of cases may protect them from seeing quite the severity that places like Italy and New York City encountered. A younger population is more likely to experience milder cases.

With a younger population come the health concerns not related to COVID19: pediatric diarrhea and pneumonia, malnutrition, HIV, TB, malaria, maternity care, acute trauma / surgical emergencies. These services don't just need to be preserved - they need to be strengthened so that the external shock of COVID disrupting the entire system does not create a ripple effect that is more damaging than the Coronavirus itself.

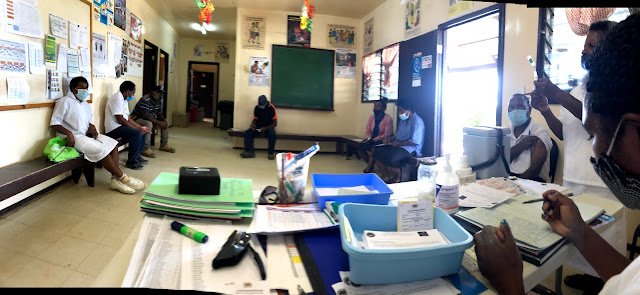

The focus on infection prevention and control should be on protecting health workers who provide all of the other vital services in these places, but cannot do so if they are sick or dying. PPE should be funneled directly to the front lines of all health facilities with surge supplies provided to places experiencing local outbreaks. Cough triage centers should mask patients, who should wear their masks anytime they are in the facility receiving care or getting diagnostics. Providers should be given medical grade masks in ample supply. Hand sanitizer is needed for providers, especially in places where running water and soap are scarce. Hygiene materials like disinfectants for environmental control throughout facilities are needed to prevent the health centers from becoming a nidus of infection, which has occurred during Ebola outbreaks in the past. National departments of health need to be active in promoting and funding the establishment of less crowded wards in health facilities which will also serve to minimize cross-contamination of other diseases like Tuberculosis.

At the community level, lock-downs are not that practical. They can buy time after a case is detected in a specific area to prepare for the next phase, but on a large scale and for a prolonged period they can be more damaging to those who are already struggling to generate enough income or food to keep their families alive. They also choke off the supply lines that are needed to maintain other essential services. Instead, a technique called "shielding" could be employed - advising those who are at highest risk like the elderly or those sick with chronic conditions that they are "safest at home" and to avoid crowded places and not receive visits from sick persons.

A major UN health agency recently offered our facility two ventilators. But those who require mechanical ventilation are likely to need it for days or even weeks. So the first two critically ill patients could be placed on ventilators and the rest would, as usual, be left without? These individuals are likely to develop other systemic problems like renal failure which we have no capacity to treat. They need to have doctors and nurses with expertise and in caregiver ratios that we cannot provide. The focus in preparation for case management should be on providing the supplemental care to the moderate or (more rarely) severe cases in the younger age groups or health workers who are likely to survive the disease who can then go on to continue providing for their children and saving lives. This means getting more oxygen-capable beds, perhaps using solar-powered oxygen concentrators, and getting them de-centralized - which will have long-lasting impacts improving childhood pneumonia survival in those areas. It might look and feel good to see exported ventilators, but it may not make a big impact at the population level.

|

| Can you spot the bananas hanging off the tall tree? Those are ventilators. |

|

| A little easier to see these - the "low hanging fruit" of strengthening the health system overall and protecting health workers |

COVID19 will dramatically alter the landscape of global health. In some places, this means a large number of graves filled by those infected with the virus. But in some it will mean a wake of gutted health systems and exhausted workers that continue their efforts to treat conditions creating the greater health burdens in their communities while having more patients cough on them. When considering how best to combat the pandemic, those with the affluence and influence to mobilize resources ought to consider where the most effective interventions truly lie.

Comments

Post a Comment