The birth of an endemic

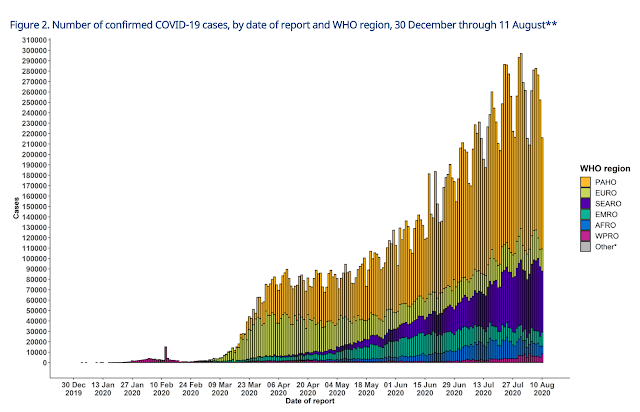

On 11th of March, 2020 much of the world started using a word previously consigned to movies and games: pandemic. The World Health Organisation declared COVID19, a disease caused by a novel Coronavirus, a pandemic due to “alarming levels of spread and severity, and … alarming levels of inaction”(1). “Pandemic refers to an epidemic that has spread over several countries or continents, usually affecting a large number of people”(2).

Many countries declared various states of emergencies and put their populations into “lockdown” mode. Travel stopped. Economies shut down. Emergency bail-outs were given in higher-income countries to keep people from going bankrupt while they shored up at home to “flatten the curve.” Health workers in several countries or cities were overwhelmed or infected but kept going and were lauded as heroes (in some places) – while wondering if they themselves would contract severe disease or run out of ventilators, and when an effective treatment might be found.

Everything got political. Do we wear masks? Do we use these medicines? Who is going to pay for all of this? Why does anyone expect us to go to work when there is a deadly disease out there?! Why did this country do so much “better” than this one? Can we protest – outside, with masks on?

Then we all wanted to “re-open” or “re-start” our economies. We can’t stay home forever. People need to keep their jobs. Work-at-home is fine for a bit, but got crazy after weeks and months. Mental health suffered and families were over-stressed. Now we don’t know if we can restart school or not.

As we look back on nearly 6 months since the declaration of a pandemic I am forced to wonder what the future will look like. What I think I see developing is rather tragic.

In the early days of the pandemic, global solidarity seemed to surge. Facebook was flooded with people concerned about this new disease – a killer – spreading like wildfire. Health workers were applauded. They were given free food. People looked at lower-income countries and felt a genuine throbbing in their heart knowing that they were already stretched and facing down yet another new disease in their vulnerable societies.

But as knowledge about the virus improved, it seemed that we could better predict who might be at higher risk for getting severely ill or dying. But it was still best to protect those vulnerable and remain at home whenever possible. We found creative ways to keep our economies limping along through curb-side pickups. We found a couple medicines with promise. The daily numbers of those infected or dying lost their “shock” value.

The case numbers in a handful of countries went down or were nearly eliminated. Yet outbreak fatigue sets in for the rest of the world and they can’t seem to eliminate this Coronavirus. The curve may flatten, but it’s still there. This isn’t going away.

But, vaccines are being developed at a rate never seen before. Billions of dollars are going into aggressive research on hundreds of candidates(3,4). Some of these are using newer tech that has enabled rapid production and acceleration to human trials. We can get rid of this thing, surely.

Not so fast.

Part of the “stun” factor that this new virus created was simply down to the fact that it penetrated higher-income countries early and quickly. In places like Europe or the U.S., infectious diseases just don’t kill that many people compared to the growing burden from non-communicables like heart disease, strokes, diabetes and cancer. When an outbreak occurs in a society that is used to being able to interact and mingle in large cities without thought for dangerous infections, it can get very scary very quickly.

So the world shuts down, takes stock, buys time and starts developing tech to combat this like crazy. But then we have to keep people working, keep kids in schools – keep on living. So we realize we cannot eradicate this disease, and we can’t quickly eliminate it either. We can simply mitigate its effects until the technology (vaccines) come around to send it the way of other infectious agents that used to plague us in significant numbers (like Measles). Herd immunity achieved through vaccination and/or naturally acquired infections will be the exit strategy.

But what about the parts of the world to which those more affluent travelers carried COVID earlier this year that are now starting to see more significant outbreaks? Places like Africa, South Asia and the Pacific? Their younger populations (a result of people suffering from numerous other health maladies causing death at earlier points in their lives) seem to protect them. The case numbers aren’t what were catastrophically expected. They are dying, but not with as much “alarm” in the numbers as people suffered in Italy. Why?

The answer is that we are witnessing the birth of a new endemic.

“Endemic refers to the constant presence and/or usual prevalence of a disease or infectious agent in a population within a geographic area”(2).

The case numbers in places with weak disease surveillance systems are not reliable. Not just due to limited numbers of tests, but the simple mechanics of conducting the test. In my country, the reagents for the test ran out quickly and samples were needing to be transported to a more affluent neighbouring country’s public health laboratory for processing. The recommended time to maintain a sample (at 2-8 degrees Celsius) is 48-72 hours … but transport and processing was taking 5-10 days. Results came back a couple weeks later. By that time, the patient has already experienced the outcome of their infection and likely already transmitted it. This kind of challenge is still present in many places. So the testing and surveillance numbers are likely dramatically under-reporting actual case numbers.

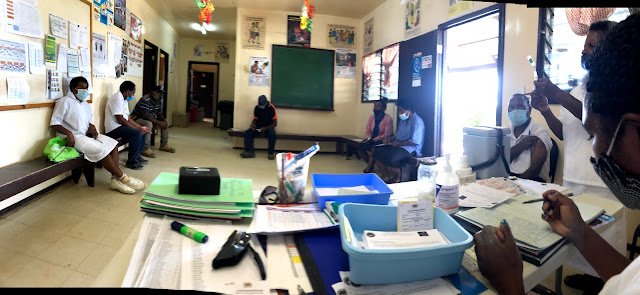

The strategies used to combat this particular infection in more affluent nations are destroying the health system capacity in places with resources already stretched super thin. To isolate, test, contact trace and repeat ad infinitum is impractical even in countries with significant health capacity … it is simply not possible in countries whose public health resources are already way behind their disease burdens. Yet this is the approach maintained by high-level organizations that are providing technical guidance the world over. Perhaps that approach needs to be re-thought.

The difficult truth is that COVID is the new endemic. In countries with weaker health systems, they will add it to the pile of diseases and ailments that they are running behind in combating. It will dominate the funding requests, grant proposals and brochures that pass from lower-income countries to the significant and powerful actors in global health – every issue being spun as a COVID-related activity because the money will otherwise be siphoned away. This is not that dissimilar from HIV – which is now mostly considered endemic in certain parts of the world. But when it comes to previously encountered infectious agents, COVID is most strikingly like Tuberculosis.

TB is a micro-organism that typically spreads through droplet (or in some cases aersolisation) transmission in close contact with those who are infected and symptomatic. For a good number of people it will not create problems, but there are about 10% of folks who will go on to develop “active” disease. The average person with active TB who coughs can transmit the disease to about 10 other people per year if they are not put on treatment. We know some of the things that make a person more likely to have active disease and we screen folks for TB based on this knowledge. There is a vaccination, though not a very good one, but there is a very effective treatment when taken appropriately. In spite of all this, TB is endemic in many parts of the world. Just when we got good at treating TB (and driving the “reproductive rate” below 1) HIV emerged and amplified its transmission and fatality potential. So the current thinking is that maybe 20-30% of people around the world have TB in their body with 10% of those having active disease. Of those with active disease, a case fatality rate of 10% is not uncommon and is significantly influenced by co-morbidities like lung disease or immuno-compromise. In our facility we diagnose about 300 new cases of active Tuberculosis each year.

Another infectious disease that COVID makes me think of is Measles. Measles is a contagious virus also spread through droplet or sometimes contact transmission. While for most it causes only fevers, cough and rash – there are those for whom it can lead to significant pneumonias and even be fatal, particularly in younger populations. This is impressively different than COVID, which has largely spared the young and afflicted the elderly with more severe disease. Measles is preventable with a very effective vaccination but the vaccination needs to be given to about 90% of the population to create herd immunity because Measles is extremely contagious – much more than Coronavirus. Yet Measles has largely been eliminated in countries with strong public health systems … and should really be high on the list of potential eradication targets to remove it from the face of the earth. In my first year here, we dealt with a profound measles outbreak, but have had 2 immunisation campaigns in the past 6 years and are probably better protected now than at any time before.

The places that still struggle with TB, Measles and other vaccine-preventable or treatable infectious diseases have in common: weak health systems, rural or difficult to access populations and a mutual neglect by the more affluent OECD countries when it comes to sharing actionable health technology resources.

So where will this all go in the end?

Until recently, most international travellers were

required to carry their “Yellow Fever” vaccination card with them anytime they

boarded a plane and crossed a border. I suspect

in 2021 there will be a very comparable COVID vaccination card required for international

travel. The vaccination will gradually

make its way through more affluent nations, especially to those most

vulnerable, and some passive infection will create herd immunity. I suspect there will be seasonal outbreaks

that decline in severity over time and the COVID vaccine might become a yearly

booster given along with influenza … “Time for your yearly FluCo” shot.

But the rest of the world will be left to continue to struggle.

The young populations will stay young – because it is just another endemic that takes away lives – but will probably be under-detected and under-measured because of quickly exhausted testing capacities and surveillance fatigue.

The long-awaited immunisation will be just another jab that feels a million miles away to populations attending health centres that are struggling to have running water and lights to deliver babies by – leave alone having enough power to keep enough vaccines cold for reliable mass utilisation.

The affluent travellers will traverse the globe with their COVID vaccination cards flying over great swathes of countries and peoples labouring under yet another tropical fever – the newest endemic.

1) https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

2) https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section11.html

4) https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines

"Let’s keep in mind that this pandemic will end. All pandemics do. Our federal government, drug manufacturers, and everyone involved in health care are working to bring that end about as soon as possible, and make COVID-19 something we can read about in history books, like other diseases that have been eradicated." - Janette Nesheiwat, Urgent Care doctor in New York, USA.

ReplyDeleteThis is the problem ... even physicians in rich countries just assume that these kinds of disease "go away". Only one disease in the history of the world has been truly eradicated: Smallpox. Every other disease ever discovered is still with us ... they are just infecting those who have no voice and suffer abusive levels of neglect by much of the world.